Dynamics Updates

Vision 2035: The need for Innovation to Meet Ambitious Targets set by the UK’s New Critical Minerals Strategy

The Government has announced the UK’s new Critical Minerals Strategy, which sets out an ambitious roadmap to secure essential mineral resources. The aim is to meet short term demand and support future development of key growth sectors for the UK’s Modern Industrial Strategy. These sectors include Advanced Manufacturing, Clean Energy Industries, Digital and Technologies, Defence and Life Sciences. Main commitments include a boost to funding and energy costs relief, as well as streamlining of environmental permitting.

The Critical Minerals Strategy lays out concrete targets to produce 10% of UK’s critical mineral needs domestically by 2035, and a further 20% through recycling. We can anticipate that a crop of innovative technologies will be developed to meet these targets, given the ever-increasing demand for mineral extraction and processing capabilities. Current activities are not sufficient.

The UK has a high level of innovation capability, and the Critical Minerals Strategy places great emphasis on leveraging this. The government aims to utilise the UK’s strong R&D landscape, including world-class universities and academic centres of research on critical minerals, to propel innovation in technologies essential to Critical Minerals. These include chemistry, metallurgy, geology, midstream processing, recycling and mining engineering. Midstream processing and recycling expertise, in particular, are identified as well-established and growing capabilities of the UK.

What role can intellectual property (IP) play in supporting those working hard to reach the ambitions targets that have been set? The Critical Minerals Strategy does not explicitly comment on IP, despite the undeniable role it will play in the years to come, both home and abroad. Any emergent technology may well become essential to one or more critical minerals sectors, and therefore have worldwide application.

The patent system requires an owner to disclose their invention in return for the right to prevent others from making use of the invention for a predetermined period of time (typically 20 years). This enables collaborative IP partnerships to be developed, while safeguarding R&D investments and encouraging further innovation. This in contrast to trade secrets that, whilst in theory are perpetual, do not enable innovation based upon the published work of others. Savvy innovators will look to protect their new ideas with IP, likely via patents and/or trade secrets. Given the potential market for successful innovations, holders of IP rights could stand to reap substantial financial benefits and collaboration opportunities. The next decade is a prime opportunity to safeguard innovations via a strong IP strategy.

The Critical Minerals Strategy stresses the importance of international partnership and collaborations, due to the inherent international distribution of natural resources and locations of existing processing capabilities, whilst highlighting that attracting investment to the critical mineral sector can be difficult due to uncertainty introduced by volatile raw material trade prices. This inherent risk can be remedied to some extent by a robust IP portfolio, supported by a deliberate IP strategy. This is because a strong IP portfolio provides intangible assets that are a health and security indicator much sought after by both public and private investors.

A prudent approach to international collaboration and risk management must always include an awareness of IP rights. Protecting those rights gives the owner control over how they are used. Domestically-originating IP may require protection abroad, in strategic jurisdictions, to allow UK businesses to retain their competitive advantage and leverage when expanding or collaborating internationally. Companies in the sector should also be aware of the present IP landscape to ensure their activities do not infringe upon the rights of others. Licensing or other contractual agreements may be needed if a company does not have freedom to operate in light of IP held by other parties. Such awareness of the IP landscape may also help identify market gaps ready to be explored by R&D, secured by IP and, eventually, capitalised on in the market.

The UK’s critical minerals strategy is a welcome recognition by the government of the role of innovation in the future of the critical minerals industry, to support the green transition, strengthen the UK’s mineral supply chain and drive key growth sectors. A thought-out IP strategy is a vital tool for businesses to demonstrate and safeguard their R&D and better reach their commercial potential.

Further reading

Department for Business and Trade. (2025). The UK's Modern Industrial Strategy. Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-strategy

Department for Business and Trade. (2025). Vision 2035: Critical Minerals Strategy. Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-critical-minerals-strategy/vision-2035-critical-minerals-strategy

EIP Guide to IP for SMEs (LINK)

Another day, another interim injunction granted by the UK High Court: Boehringer Ingelheim find success against Dr Reddy

Michael Tappin KC (sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court) has granted the interim injunction sought by Boehringer Ingelheim Internation GmbH (“BI DE”) against Dr Reddy’s (UK) Limited (“DR”). The injunction will remain in place until the form of order hearing following judgment after the revocation trial brought by DR, which is scheduled for October 2026. This decision reflects the Court’s continuing approach that maintaining the status quo is currently best achieved by granting injunctions.

BI DE is the holder of the UK marketing authorisations for Jardiance. A medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, which is based on empagliflozin (a SGLT2 inhibitor). BI DE is the proprietor of a number of patents relating to empagliflozin.

DR began corresponding with BI DE in March 2024 regarding the invalidity of two patents (and the related SPC) covering empagliflozin. In October 2024, DR issued a revocation action against BI DE. However, the claim form and accompanying pleadings were not served until February 2025. DR obtained a marketing authorisation for empagliflozin following the expiry of marketing exclusivity in May 2025. At the July 2025 CMC, a trial was fixed for October 2026 with DR indicating that its launch plans were still under discussion.

On 18 September 2025, DR gave 28 days’ notice of its intention to commence sales of its empagliflozin products in the UK. This was the trigger point for BI DE to apply for an interim injunction against DR. The proposed interim injunction was expected to last at least 14-15 months, which, in turn, would have been the amount of time that DR could be on the market ahead of trial, if the injunction had not been granted.

As is usual with injunction applications of this kind, the facts of each case are very specific and taken into consideration when the Court looks to apply the guidelines set out in American Cyanamid v Ethicon when assessing whether an injunction should be granted or not.

The evidence before the Deputy Judge included evidence from commercial managers of the parties, pharmacists, clinicians and expert evidence from economists and ran to approximately 300 pages (excluding exhibits). But yet, despite the length, there was very little evidence to explain DR’s conduct in the litigation. DR explained that its decision to launch its empagliflozin product so quickly was tied to the dapagliflozin litigation (another SGLT2 inhibitor), following the invalidation of AstraZeneca’s compound patent for dapaglifloxin and then the Supreme Court’s refusal of AstraZeneca’s permission to appeal on 31 July 2025. The Deputy Judge noted that DR’s failure to prepare for the dapagliflozin market becoming generic and adapting its litigation strategy accordingly was a contributing factor to his decision, citing Lord Justice Arnold’s reasoning in his Court of Appeal judgment in Astrazeneca v Glenmark [2025] EWCA Civ 480.

As an aside, the Deputy Judge granted permission to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care to intervene, serve evidence and make submissions. The statements were served by the head of the Medicines Framework and Reimbursement team from within the Medicines Directorate in the Department of Health and Social Care (the "DHSC"). The Deputy Judge made it clear that he found the evidence an extremely valuable account of the pricing and reimbursement system operated by the DHSC and that any court hearing an application for an interim injunction in a pharmaceutical patent case would benefit greatly from reading it.

Two points to note from this judgment is that, first, the current case law makes it clear that a generic will need to take effective steps to clear the way, and, where necessary, anticipate any changes to their relevant market if that may suddenly become a factor as to changing their launch plans.

Second, the volume of evidence before the court may soon become standard practice, particularly with the increasing use of expert economic evidence. This may be another factor to keep in mind when developing a strategy for this type of application.

The judgment is available here.

Vision 2035: The need for Innovation to Meet Ambitious Targets set by the UK’s New Critical Minerals Strategy

The Government has announced the UK’s new Critical Minerals Strategy, which sets out an ambitious roadmap to secure essential mineral resources. The aim is to meet short term demand and support future development of key growth sectors for the UK’s Modern Industrial Strategy. These sectors include Advanced Manufacturing, Clean Energy Industries, Digital and Technologies, Defence and Life Sciences. Main commitments include a boost to funding and energy costs relief, as well as streamlining of environmental permitting.

The Critical Minerals Strategy lays out concrete targets to produce 10% of UK’s critical mineral needs domestically by 2035, and a further 20% through recycling. We can anticipate that a crop of innovative technologies will be developed to meet these targets, given the ever-increasing demand for mineral extraction and processing capabilities. Current activities are not sufficient.

The UK has a high level of innovation capability, and the Critical Minerals Strategy places great emphasis on leveraging this. The government aims to utilise the UK’s strong R&D landscape, including world-class universities and academic centres of research on critical minerals, to propel innovation in technologies essential to Critical Minerals. These include chemistry, metallurgy, geology, midstream processing, recycling and mining engineering. Midstream processing and recycling expertise, in particular, are identified as well-established and growing capabilities of the UK.

What role can intellectual property (IP) play in supporting those working hard to reach the ambitions targets that have been set? The Critical Minerals Strategy does not explicitly comment on IP, despite the undeniable role it will play in the years to come, both home and abroad. Any emergent technology may well become essential to one or more critical minerals sectors, and therefore have worldwide application.

The patent system requires an owner to disclose their invention in return for the right to prevent others from making use of the invention for a predetermined period of time (typically 20 years). This enables collaborative IP partnerships to be developed, while safeguarding R&D investments and encouraging further innovation. This in contrast to trade secrets that, whilst in theory are perpetual, do not enable innovation based upon the published work of others. Savvy innovators will look to protect their new ideas with IP, likely via patents and/or trade secrets. Given the potential market for successful innovations, holders of IP rights could stand to reap substantial financial benefits and collaboration opportunities. The next decade is a prime opportunity to safeguard innovations via a strong IP strategy.

The Critical Minerals Strategy stresses the importance of international partnership and collaborations, due to the inherent international distribution of natural resources and locations of existing processing capabilities, whilst highlighting that attracting investment to the critical mineral sector can be difficult due to uncertainty introduced by volatile raw material trade prices. This inherent risk can be remedied to some extent by a robust IP portfolio, supported by a deliberate IP strategy. This is because a strong IP portfolio provides intangible assets that are a health and security indicator much sought after by both public and private investors.

A prudent approach to international collaboration and risk management must always include an awareness of IP rights. Protecting those rights gives the owner control over how they are used. Domestically-originating IP may require protection abroad, in strategic jurisdictions, to allow UK businesses to retain their competitive advantage and leverage when expanding or collaborating internationally. Companies in the sector should also be aware of the present IP landscape to ensure their activities do not infringe upon the rights of others. Licensing or other contractual agreements may be needed if a company does not have freedom to operate in light of IP held by other parties. Such awareness of the IP landscape may also help identify market gaps ready to be explored by R&D, secured by IP and, eventually, capitalised on in the market.

The UK’s critical minerals strategy is a welcome recognition by the government of the role of innovation in the future of the critical minerals industry, to support the green transition, strengthen the UK’s mineral supply chain and drive key growth sectors. A thought-out IP strategy is a vital tool for businesses to demonstrate and safeguard their R&D and better reach their commercial potential.

Department for Business and Trade. (2025). The UK's Modern Industrial Strategy. Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-strategy

Department for Business and Trade. (2025). Vision 2035: Critical Minerals Strategy. Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-critical-minerals-strategy/vision-2035-critical-minerals-strategy

Research underlying Nobel prize in Chemistry has sparked innovation and patent filings

Imagine a material that can capture water vapour from desert air during the night and then release water when the sun rises – this sounds like science fiction but has become a reality by the research made by Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar M. Yaghi, awarded the Nobel prize in Chemistry 2025.

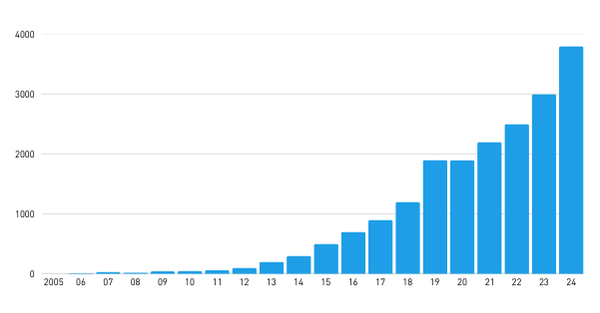

This year’s laureates have created a new type of molecular entities, metal-organic frameworks, MOFs, with enormous potential. Besides water harvesting, future application areas include e.g. gas storage, water purification, carbon dioxide capture, and battery technology. The number of patent publications relating to MOFs has risen from close to zero in 2005 to near 4,000 in 2024.

Metal-organic frameworks, MOFs, are materials in which metal ions (or clusters) are connected by organic linkers to create a 3D network containing a vast number of well-defined cavities. The cavities can act as reservoirs for guest molecules that can enter and exit from the surrounding environment. The seemingly endless combinations of the building blocks (metal and linker) allow precise tailoring of MOF properties, such as cavity size and chemical functionality, to suit specific applications.

Source: © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

MOFs are highly porous materials with exceptionally large internal surface areas. One gram of a MOF could have an internal surface area as big as a football field! This makes MOFs better adsorbents than previously known porous materials, such as zeolites or activated carbon.

The MOF technology has paved the way for a flood of innovations in various industrial sectors, such as e.g., chemical industry, healthcare & pharmaceuticals, energy, and environmental remediation.

The vast innovative activity is mirrored by the steep increase in patent filings in the MOF field. China shows the highest patent filing activity, followed by the US and South Korea. A large part of the patent application filings stem from universities, but also major companies like BASF and ExxonMobile can be found among the top filers.

Credit: CAS Content Collection

(Michael McCoy Chemical & Engineering News, May 27, 2025: “Eye on Patents: Powering EVs and capturing CO2 with metal-organic frameworks”)

Considering the steep rise of patent applications relating to MOFs, it is evident that this field attracts a lot of interest, both in academia and industry. The Nobel laureates themselves also have their research work protected by several patents.

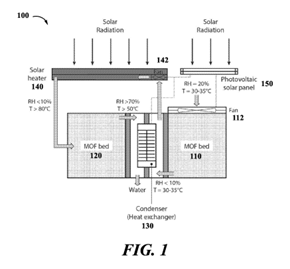

Omar M. Yaghi (together with fellow inventors) has a patent relating to a moisture harvester containing a MOF as water capturing material. This allows liquid water to be collected, also from dry air, e.g. in desert environments. The collected water is suitable for human consumption and can also be used for irrigation of crops. It is easy to envision the impact this invention may have for populations in areas where water supply is scarce.

(Fig. 1 from EP 3837399 B1 – representative patent family member)

Susumu Kitagawa (and fellow inventors) holds a patent relating to a method for separating and storing highly unstable per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), such as tetrafluorethylene, through adsorption to a MOF. PFAS are widely used industrially, and the possibility to separate, store and transport these toxic and hazardous molecules in a safe way is of great value for humans and the environment.

(Fig. 9 from EP 3339281 B1 – representative patent family member)

The MOF science is still new, and the broad use and application of MOFs in an industrial scale are yet to be explored. In times of climate change and sustainability challenges, they at least bring a fair amount of hope and expectations to the table.

The scientific community is excited that the basic research behind MOFs is being awarded the Nobel prize, and Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar M. Yaghi have surely inspired to continued ground-breaking research and innovation. Who would not want to join the solemn Nobel prize ceremony and dinner in beautiful Stockholm?

When is a managing director an accomplice to patent infringement?

Philips v Belkin

UPC_CoA_534/2024, UPC_CoA_19/2025 and UPC_CoA_683/2024, decision of 3 October 2025[1]

This is an appeal against a finding of infringement by Belkin of Philips’ patent relating to wireless inductive power transfer, and against the dismissal of Belkin’s counterclaim for invalidity. In addition to injuncting several Belkin group companies, the first instance judgment ordered the managing directors of Belkin to “refrain from performing their services as managing director . . . in such a way that the patent-infringing acts are carried out” as accomplices to the infringement. It did not, however, injunct the managing directors more generally (i.e. if they were to start a new company to carry on infringement) or require any payment of damages by the directors.

Both Belkin and Philips appealed. Belkin requested that both decisions be set aside in their entirety, the infringement proceedings to be dismissed, and the patent to be revoked in Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden. Belkin also expanded its arguments on first instance and claimed for the first time invalidity due to lack of inventive step. Philips requested that Belkin’s managing directors be ordered to cease and desist, provide further information and to pay damages, as well as requesting that Belkin pay the costs of the case and extend the recall following the finding of infringement.

The Court of Appeal dismissed Belkin’s request for dismissal of the counterclaim for revocation. In doing so, they did substantially consider Belkin’s new arguments, stating that they were “a matter of different understanding of disclosure passages in a document of the prior art on which Belkin had already based its argumentation in the first instance”, and that Phillips had sufficient opportunity to comment.

The Court of Appeal also dismissed Belkin’s appeal against the finding of infringement against the Belkin group companies. However, the Court did dismiss the order against the managing directors, finding that their activities were not sufficient to establish themselves as accomplices. The Court clarified that for a managing director to be an accomplice, they must either deliberately use the company to commit patent infringement, or if they are aware that the company is committing patent infringement, aware that the act of use is illegal, and takes no action to stop the infringement

[1] https://www.unifiedpatentcourt.org/en/node/149310