The people, physics and patents of the 2025 Nobel prize

The Nobel Prize in physics 2025 was awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis “for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit” [1]. Their discovery paved the way for the race to achieve a working quantum computer and quantum supremacy – demonstrating a programmable quantum computer can solve a problem infeasible for any classical computer. Thus, the three physicists are rightfully rewarded for showing a phenomenon that provides a significant source of technical innovation today. Interestingly, Clarke, Devoret and Martinis have also been prolific in patenting their findings and technologies and getting on the deep tech patent train, probably before the word was even invented. In the light of the Nobel ceremony, this article will dive into the people, physics and patents of macroscopic quantum tunnelling (MQT).

Bringing quantum tunnelling to the macroscopic scale

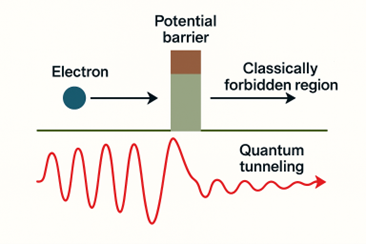

Let’s start with an overview of the science. As many of us know, a classical particle in a potential well, for example a golf ball in a cup, will never leave the well unless energy is brought into the system. For the golf ball, this might mean lifting it out of the cup. However, a particle governed by the laws of quantum mechanics may spontaneously leave a potential well without any addition of energy to the system, in a phenomenon called quantum tunnelling. This happens for tiny particles such as electrons and has been a well-known phenomenon for decades. Simplifying somewhat, the probability and strength of quantum tunnelling can be said to be inversely proportional to the size of the system. As illustrated in Figure 1, the probability of the particle existing outside the potential well is smaller, but not zero, and reduces with the size of the system. Once the effect had been demonstrated for the electron, the question became how large a system could become before the probability of quantum tunnelling becomes negligible, and the search for a system exhibiting MQT was inevitable.

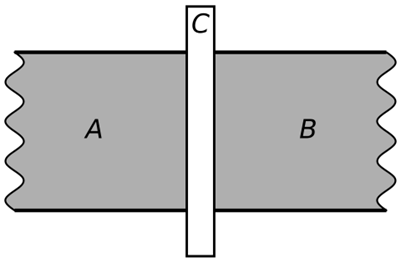

Physicists discovered a candidate for MQT in superconducting circuits. One such circuit is called a current biased Josephson junction, illustrated in Figure 2, formed from two superconducting leads (A and B) separated by a potential barrier (C).

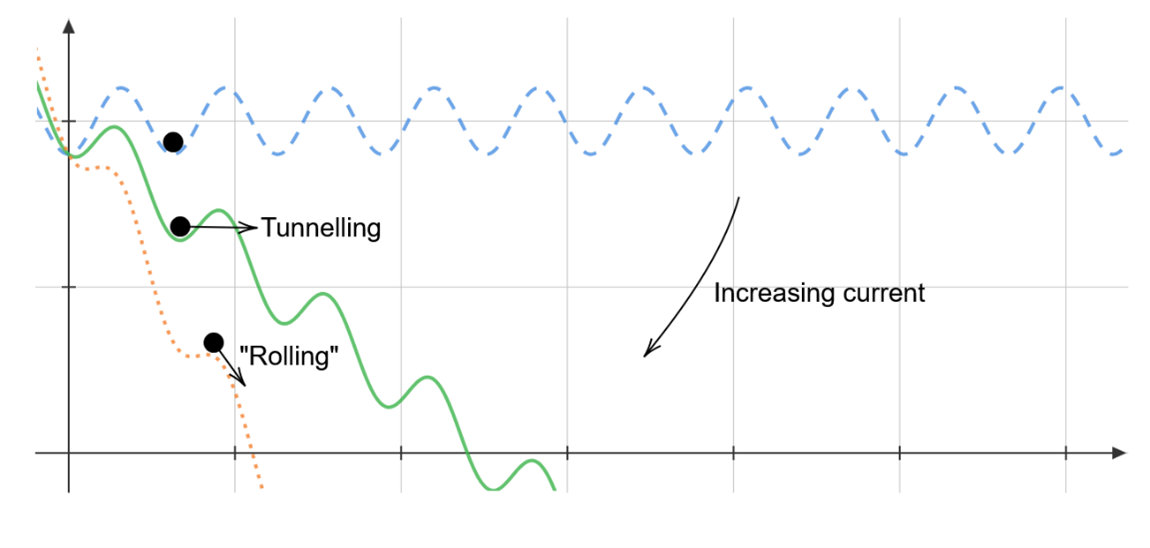

According to the BCS theory of superconductivity, pairs of electrons may bind together at sufficiently low temperatures, forming what is known as Cooper pairs. The theoretical potential seen by Cooper pairs at C will be of the shape of a tilted washboard as shown in Figure 3. At zero current, the Cooper pair (depicted as a black ball) cannot move. When the bias current over the Josephson junction increases, it may tunnel through the barrier, and no voltage will be seen between A and B. As the current further increases, the potential will be so steep that even a classical particle may “roll” down the potential, and a voltage will be seen between A and B. The current where a voltage can be seen across the junction is called the critical current.

In the beginning of the 1980s, experiments were performed to experimentally verify this behaviour. When the bias current across a Josephson junction was increased gradually, a critical current could indeed be detected. However, there was uncertainty regarding whether this effect was due to disturbances in the circuit, noise or true superconductivity.

When John Clarke was working at the University of California, he formed a group with his doctoral student John Martinis and post-doc Michel Devoret to conduct a series of experiments that finally confirmed, beyond reasonable doubt, that the effect seen in the Josephson junction indeed was MQT. They showed that a circuit “big enough to get one’s grubby fingers on” [1] could be made to exhibit quantum tunnelling. This laid the groundwork for the decades of work on quantum computing and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that followed.

A case study of deep tech patents

The three physicists continued working on applications for Josephson junctions, many of which have been patented. A search for patents attributed to at least one of the laureates reveals 53 patent families totalling 434 patents across the world. The most significant portion of the families, 23 of them, are attributed to Martinis and collaborators. Yale University owns 18 families, while 16 are owned by Google and mostly relate to Martinis’ work with quantum computing, and 11 by the University of California. Let’s dive into two of them relating to MRI.

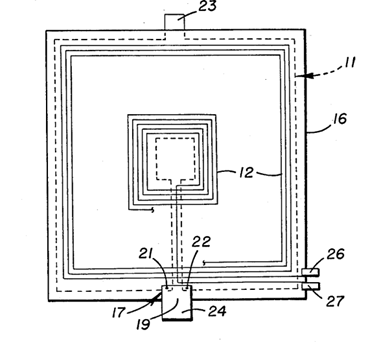

An early patent attributed to Clarke, Martinis and Claude Hilbert, US patent 4585999 A, claims priority in April of 1984. The patent concerns an amplifier based on a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) and was owned by the US Department of Energy. The device comprises two Josephson junctions, showing its practical applicability at an early stage. It is mentioned in the patent that the device “would have particular use in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging”, also known as MRI.

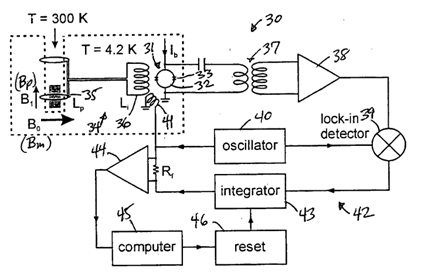

Fast-forwarding a few years, a patent attributed to Clarke and collaborators claiming priority in February 2002, EP1474707B1, indeed concerns “SQUID detected NMR and MRI at ultra low fields”. MRI is normally performed at magnetic field strengths around 1-10 T, while the patent describes NMR using fields in the micro tesla range using a SQUID as a magnetometer, shown as 33 in Figure 5. This is in the same range as the magnetic field of the Earth. Such a device would thus be able to detect the miniscule fields produced by nuclei excited by micro tesla fields while simultaneously distinguishing them from noise and the Earth. Although MRI at ultra low fields is uncommon today, this may create the opportunity to build portable MRI machines in the future, increasing the availability of this ground-breaking technology.

Conclusion

In summary, after demonstrating beyond reasonable doubt that MQT exists, the three physicists went on to develop their techniques into something applicable. These patents show that the laureates of this year’s Nobel prize were on the case of deep tech patents even before the word was invented. Being active and claiming the rights to your inventions remains important today. If you have the opportunity to do so, take the chance. We at EIP, specialising in complex and high-value patents, would be happy to help you.

References

[1] Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, “The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025,” 7 October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2025/10/press-physicsprize2025-2.pdf.

[2] Wikimedia Commons, “File: Single josephson junction.svg,” 2 September 2020. [Online]. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Single_josephson_junction.svg&oldid=446854302. [Accessed 27 November 2025].

The Latest Thought Leadership pieces in the Content Hub

The Patent Strategist

Get expert insights and the top patent stories delivered straight to your inbox.