Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v. Meril Gmbh & Meril Life Sciences Pvt Ltd.

(Infringement action UPC_CFI_15/2023)

Decision of 15 November 2024 (ORD_598479/2023[1])

The Munich Local Division (MLD) decided in favour of patentee Edwards Lifesciences Corporation (Edwards) with regard to the infringement action in respect of EP 3 646 825 (EP’825) and ordered the defendants Meril Gmbh and Meril Life Sciences Pvt Ltd. (Meril) to cease and desist from certain activities in relation to its recently launched transcatheter heart valve and related delivery apparatus. In addition to aspects specific to the facts of this case, the Decision contains some noteworthy points relating to claim construction, conduct of parties and UPC competence.

EP’825, relating to prosthetic heart valves, was maintained in amended form by the Paris Central Division of the UPC (CDP) in July 2024 as reported by us here . A revocation action brought by Meril’s Italian subsidiary and counterclaims for revocation by the defendants in the proceedings being discussed here were consolidated before the CPD. CPD maintenance decision is already the subject of an appeal so the final word on this matter is yet to be had.

Gold Standard Technology

Prior to minimally invasive TAVI (Transcatheter Heart Valve Implantation) technology, represented by the valves involved in this matter, the treatment standard involved much more invasive and risky surgical removal of the native heart valve and implantation of an artificial valve.

| Edwards` "SAPIEN" valves are the most widely used valves for TAVI procedures worldwide. | Meril recently entered the European market with the "Octacor" valve, and the associated delivery systems with the designations "Navigator" and "Navigator Inception" (referred to in the decision as "infringing embodiment"). |

|  |

In 2019, Meril launched a transcatheter heart valve, Myval along with the Navigator delivery system, and these products have been the subject matter of various infringement proceedings and cease and-desist-undertakings in Europe. Interestingly, for patients with extra-large annuli, the XL-sized Myval valve from Meril sometimes still seems to be the best option and Edwards has established a system allowing doctors to request the use of an XL valve of the Myval type if they consider it clinically necessary, even though Edwards is not legally obliged to do so, and an exception to the injunction or seize-and-desist undertaking can be granted.

Claim Construction & Infringement

The Court reiterated principles from previous UPC judgements that the patent claim is not only the starting point, but also the decisive basis for determining the protective scope of the European Patent. It is important to note that the interpretation of a patent claim does not depend solely on the strict, literal meaning of the wording used. The description and drawings must always be used as explanatory aids for the interpretation of the patent claim. However, this does not mean that the patent claim serves only as a guideline and that its subject matter may extend to what the patent proprietor has contemplated from a consideration of the description and drawings. These principles for the interpretation of a patent claim apply equally to the assessment of the infringement and to the validity of a European patent.

In order to make an accurate assessment, it is also necessary to consider the perspective of a person skilled in the relevant field. In this case, the Court defined the skilled person as a group comprising a medical device engineer with expertise in prosthetic heart valves and an interventional cardiologist.

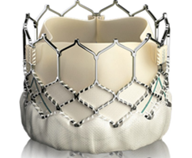

Edwards is asserting infringement of claims 1, 2, 4 and 5 of EP’825 as upheld by the CDP. Claim 1 requires the frame of the valve to be made entirely of hexagonal cells, wherein each hexagonal cell is defined by six angled struts including two opposing side struts extending parallel to a flow axis of the valve, and wherein the frame does not include any struts that do not form part of one of the hexagonal cells, except for struts that extend axially away from the inflow or outflow end of the frame for mounting the frame.

The main points of contention for claim construction and infringement centred around whether Meril’s valves had angled struts forming a plurality of hexagonal cells as required by the claim 1.

Edwards asserted that the cells in the Myval Octacor valve are hexagonal in shape corresponding to what is disclosed in Fig. 6 of EP’825. According to Edwards, the upper and lower pairs of angled struts of the attacked Myval Octacor heart valve are connected by side struts that are convexly shaped with a hole in the middle. Each cell of the attacked Myval Octacor valve therefore have six struts including two side struts that extend in the axial direction. The side struts in the upper row of cells would be formed in three instances by commissure struts which allow for a secure anchoring of the valvular leaflet structure. Edwards submitted that it is clear that the Myval Octacor valve displays the contested features.

Meril contested infringement asserting that the frame of the Myval Octacor heart valve is composed of octagonal cells that partially overlap to form rhombic cells in the overlapping zone and, in three cases, the rhombic cells in the upper row would be substituted by commissure posts that do not form struts. According to Meril, it is therefore clear that the Myval Octacor heart valve does not exhibit the features set out in claim 1 of EP '825 as upheld.

The Court considered that the term “strut” is understood in the patent at issue to mean an individual, distinct piece that is connected to neighbouring struts in connecting areas or apices. The Court used the patent description, CDP decision and also the technical understanding as applied by Meril itself in its post-filed and post-published Indian patent application 202121047196 ([00126] of IN’196) to interpret the claims.

According to claim 1, side struts that form part of a hexagonal cell extend in parallel to a flow axis of the valve, i.e. in the longitudinal direction. The Court held that a parallel orientation of the side strut relative to the flow axis requires that the two end points of the struts be positioned on the longitudinal axis of the valve. It is not required, however, that the thickness of the side strut does not vary along the extension of the side strut in the direction of the flow axis.

The Court disagreed with Meril and concluded that the Myval Octacor heart valve does not display octagonal cells; rather, it comprises and is exclusively made of hexagonal cells. The side elements which comprise an opening in the middle, are side struts that extend in the direction of the flow axis. The figures provided by both parties were also considered to demonstrate that the crimping behaviour of the frame of the Myval Octacor valve is consistent with that of a frame comprising solely hexagonal cells.

The Court, therefore, held that attacked embodiment makes direct and literal use of the patent, as upheld by the CDP. As a result, the relief sought was granted.

Public Interest Defence Rejected

Meril asserted that third parties' interests or the public interest (specifically, the life and health of patients with severe heart disease (aortic valve stenosis)) necessitate a denial of injunctive relief, recall, and destruction. Meril contended that its product offered significant advantages over Edwards' product, and it was essential to practitioners that they have a range of options for treatment. They also submitted that, in any case, injunction must not be ordered regarding the system comprising the Meril products in the sizes in which Edward’s Sapien products are not available.

The Court set out that Article 64(4) of the UPCA explicitly mentions the interests of third parties. While UPC Agreement and Regulations do not explicitly mention the interests of third parties or the public otherwise, the Court noted that interests may also be considered when exercising the discretion stipulated by the "may" in Articles 63(1) and 64(1) UPCA. In considering the interests of third parties and the public interest, the court will give due consideration to the possibility of the infringer entering into a license agreement or initiating meaningful discussion. However, the Court considered this unlikely due to interaction between parties in German national proceedings relating to a previous version of Myval valve where Meril had not made sufficient efforts to obtain a license and had declined to comply with Edwards' reasonable request for access to samples and documentation that would have enabled Edwards to form an impression of the Myval valve.

Moreover, the Court also considered that clinical needs are met by current arrangements with regard to doctors being able to request the previous Myval XL valve which is not the subject of these proceedings and it is not sufficient for a public interest to be legally justified on the grounds that it would be advantageous for the treating physician to have a variety of treatment methods at their disposal. Consequently, to justify a public interest in the availability of the infringing embodiment, it is essential to demonstrate that this is the sole available treatment method or that it represents an improvement upon a known treatment method, resulting in a notable enhancement in patient care. Hence, the public interest defence was also unsuccessful.

Competence to Adjudicate on pre-UPC Activities

Meril argued that the UPC is not competent to adjudicate claims based on activities commenced before 1 June 2023. The Court disagreed.

It was held that the UPC has jurisdiction over acts of infringement committed before the entry into force of the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court on 1 June 2023. The Court considered this to be in line with Article 3(c) and 32(1)(a) UPCA and also supported by the fact that the concurrent competence of the UPC and the courts of the member states on European patents will cease after the interim phase. Subsequently, the UPC will have exclusive jurisdiction over all European patents. If Meril's argument were to be accepted, it would mean that no court, whether the UPC or those of the member states, would have the authority to adjudicate claims for damages for infringements committed prior to 1 June 2023. This is not a viable proposition in the Court’s view, even if the statute of limitations is taken into account, because the statute of limitations only applies if the defendant raises it in a timely manner.

Court’s view on Meril’s Strategy

Meril requested a stay of the infringement proceedings on the basis that the CDP decision on revocation did not address several of its nullity arguments. The Court disagreed and stated, when commenting on the exercise of its discretion, that “Meril made a false claim that the CDP had not addressed major nullity arguments in its decision”. The Court pointed to several nullity arguments raised by Meril that had, in fact, been explicitly addressed in the CDP decision and also reasoned that decision by the CDP must be read with a mind willing to understand. Thus, arguments that are addressed implicitly are meant to and are in fact covered by the decision, as well. Meril further failed to demonstrate that the decision by the CDP is manifestly and prima facie erroneous in a material way.

In considering the exercise of discretion, the Court also stated that “… most importantly, the Meril Group attempted to outmaneuver the different divisions of the Unified Patent Court by creating a new entity, "Meril Italy", with the intention of filing a standalone nullity action with the CDP in order to disrupt and/or prolong the infringement proceedings. Despite the CDP's dismissal of Edwards' preliminary objection on the grounds of these circumstances, as evidenced by the JR´s order dated 13 November 2023 (App_572915/2023 UPC_CFI_255/2023), the Unified Patent Court should refrain from entertaining such strategic maneuvers.”

Conclusion

This Decision, largely following Edwards’ arguments, while criticising Meril’s conduct in a) claiming its nullity arguments were not sufficiently addressed in revocation proceedings before CDP and b) in starting separate revocation proceedings through its Italian subsidiary, is clearly a battle won for Edwards. However, the final chapter is yet to be written as the CDP decision to maintain the EP’825 in amended form is under appeal and this decision is also open to appeal.

The Court’s comments regarding Meril’s strategy appear instructive in terms of how certain strategic manoeuvres can count against a party when it comes to the Court exercising its discretion.

The Court has followed previous UPC case law when it comes to claim interpretation and, arguably, gone further by considering Meril’s submissions on its own later Indian application for technical understanding and claim construction on a crucial point. Perhaps this provides another hint regarding use of statements made during prosecution in claim interpretation.

We continue to watch this matter and the broader dispute relating to this technology, involving several patents and fora including the EPO, with interest.